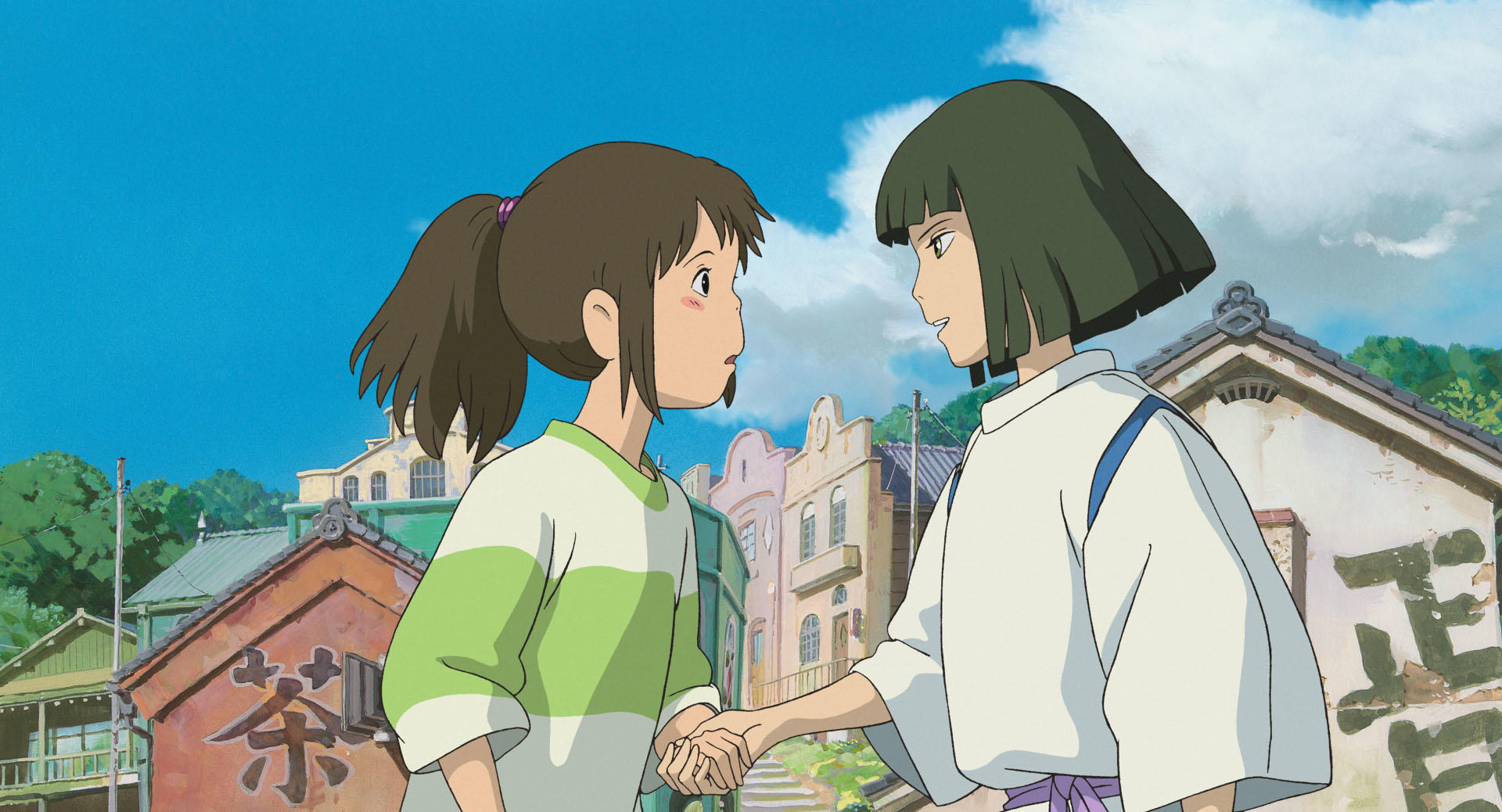

Few animated films captivate global audiences like Spirited Away, the iconic masterpiece from Studio Ghibli. Though widely celebrated for its enchanting animation and imaginative storyline, there’s far more beneath the surface than meets the eye.

In Part 1 of this series, we introduced the film’s premise and characters. Now, in Part 2, we’ll plunge deeper into its lesser-known lore, including possible hidden meanings, real-world inspirations, and the abundant rumors swirling around this landmark of Japanese cinema.

Spoiler Alert: We’ll explore plot details and behind-the-scenes stories that could spoil the magic for first-time viewers. If you prefer to experience the film fresh, bookmark this article for later. Otherwise, read on to discover the hidden layers that make Spirited Away an enduring classic.

The Aburaya “Brothel” Theory—Social Commentary or Overreach?

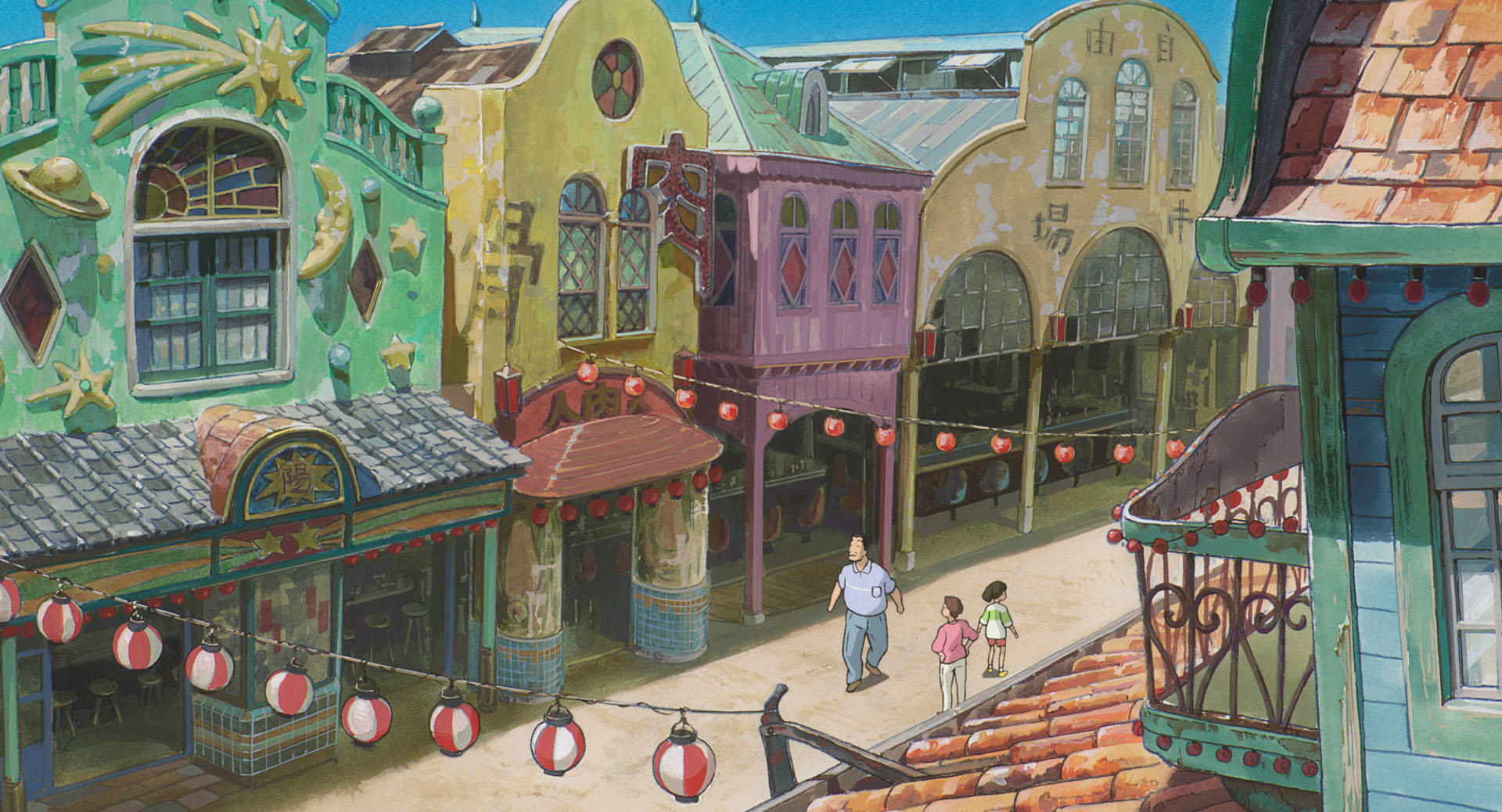

One of the most debated aspects of Spirited Away is whether the bathhouse, known as Aburaya, symbolizes a brothel. Historically, the Japanese term “yuna” (bathhouse girl) sometimes referred to women in red-light districts. Interestingly, director Hayao Miyazaki mentioned in a 2001 interview that the film reflects a society increasingly driven by consumerism, hinting at parallels to modern-day service industries.

While there’s no definitive statement from Studio Ghibli labeling Aburaya as a literal brothel, the idea remains popular among fans who interpret the bathhouse’s strict hierarchy and the characters’ money-obsessed interactions as a broader critique of exploitative workplaces.

Key Insight: Whether you see Aburaya as an allusion to historic courtesans or a metaphor for Japan’s “black companies” (exploitative employers), Spirited Away doesn’t shy away from highlighting the perils of greed.

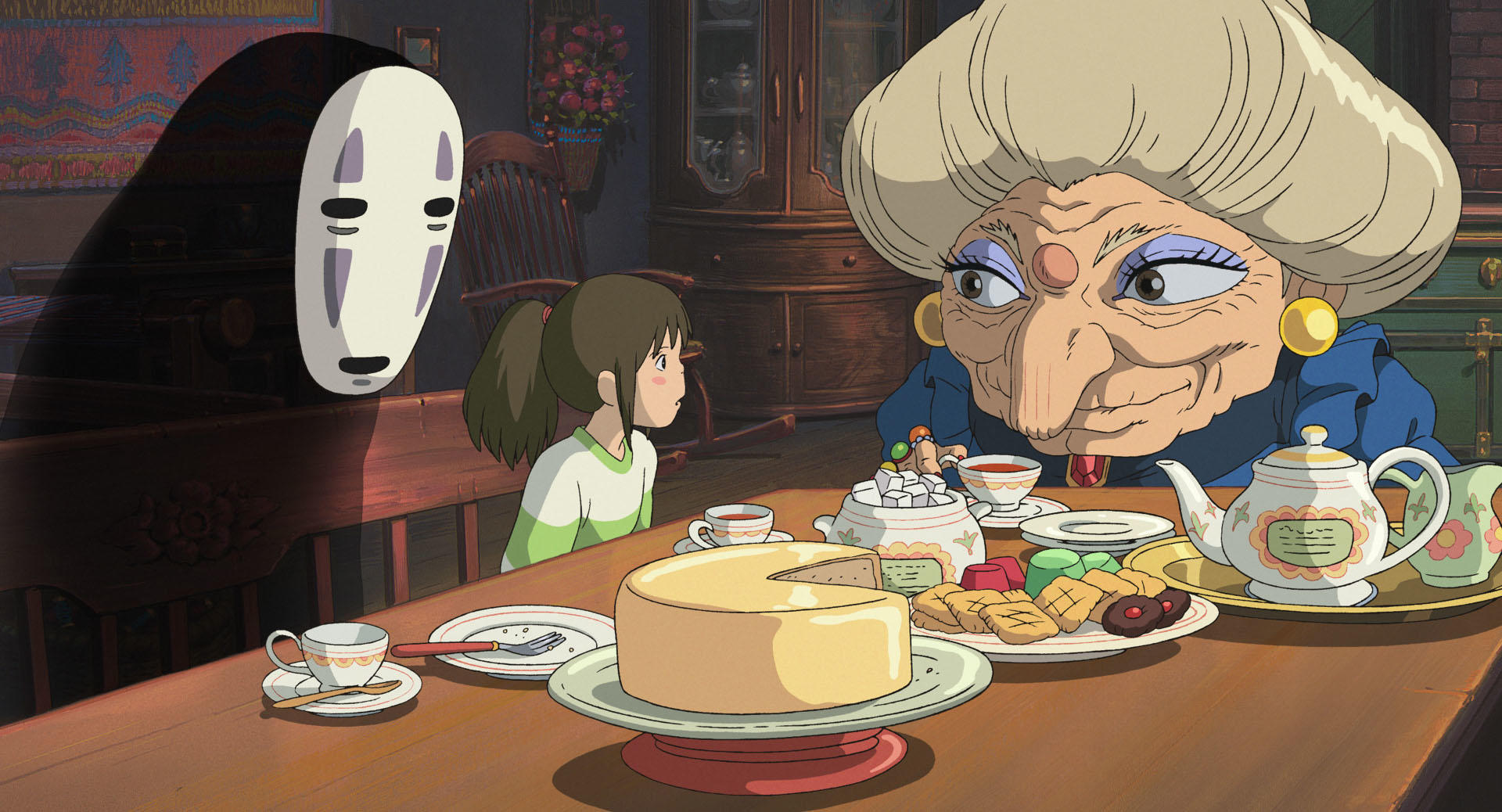

Kaonashi (No-Face)—Embodiment of Modern Greed

Kaonashi, or No-Face, stands apart from other spirits in the film for his eerie silence and unsettling transformations. Many interpret Kaonashi as a reflection of human obsession—craving attention, offering gold, and eventually devouring everything in sight.

This interpretation resonates with a world often driven by money and possessions. Kaonashi literally offers wealth to buy acceptance, only to spiral into chaos when his generosity fails to earn genuine friendship. Sen (the name given to Chihiro at the bathhouse) is the only one who rejects his bribes, hinting that genuine compassion triumphs over materialism.

Why It Matters: Kaonashi’s rampage underscores how quickly unchecked desire can morph into something monstrous—a compelling allegory for modern consumer culture.

The Alternate Ending Rumor—Fact or Fiction?

Fans in Japan often share a rumor about a “lost ending” where Chihiro momentarily remembers Haku after crossing the tunnel back to the human world. In the officially released version, she steps outside with her parents, who remain oblivious to their magical detour.

So, does an alternate scene really exist? Studio Ghibli has never confirmed this, but the rumor persists—possibly fueled by the film’s dreamlike feel. Whether it’s an example of the “Mandela Effect” or wishful thinking, the suggestion of a different finale adds extra mystique to Spirited Away.

Traces of “Beyond the Mist”—A Potential Inspiration

An oft-cited influence on Spirited Away is the children’s novel Kiri no Mukō no Fushigina Machi (“The Mysterious Town Beyond the Mist”). In it, a girl enters a strange town filled with peculiar residents, loosely mirroring Chihiro’s journey. While not an officially credited source, fans draw parallels, speculating that Miyazaki adapted thematic elements.

Regardless of whether this novel served as a blueprint, Miyazaki is known to fuse multiple inspirations into his storytelling. This complexity underscores how Ghibli films can feel both familiar and utterly unique.

Aburaya as a Symbol of Labor Pressures

Beyond the brothel theory, another common interpretation views Aburaya as representing modern “black companies.” The oppressive boss (Yubaba), extended working hours, and exploitative contracts—symbolized by employees losing their real names—can seem strikingly similar to harsh corporate work cultures.

Amid colorful visuals and fantasy elements, the film’s depiction of strict rules and punishing schedules feels startlingly real. This duality is part of Spirited Away’s charm, blending whimsical elements with a sobering look at how people survive demanding environments.

Echoes of Japan’s Economic Bubble

Released in 2001, Spirited Away emerged after Japan’s “lost decade”—a tumultuous period following the collapse of its economic bubble. Many see traces of that event in Chihiro’s parents’ overindulgence. Their transformation into pigs spotlights the destructive potential of greed, implying that unbridled consumption can lead to dire consequences.

Then vs. Now: Although the bubble burst decades ago, the film’s cautionary message about materialistic culture remains relevant worldwide, reminding viewers that prosperity can be fleeting when driven by excess.

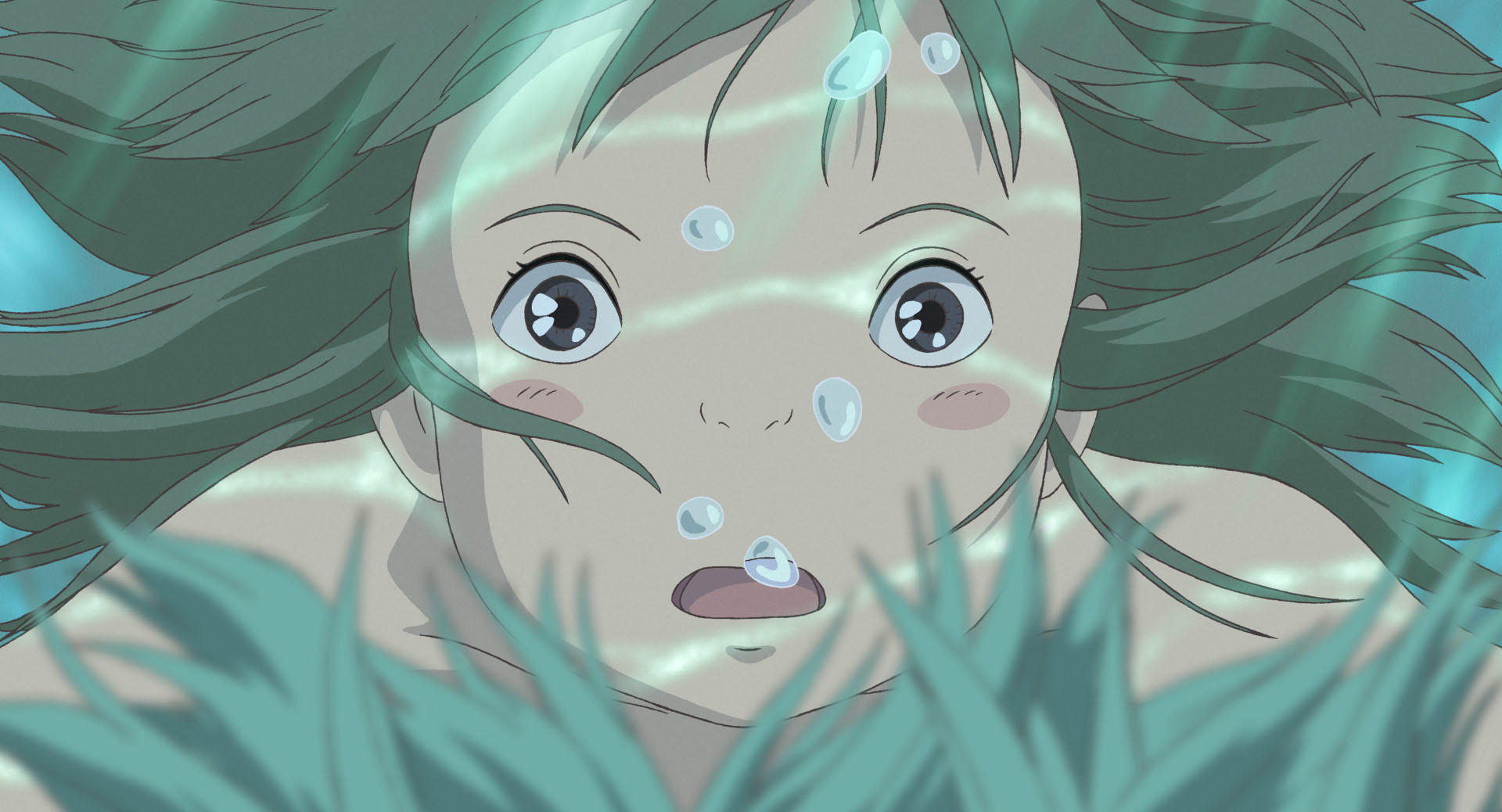

The Enigma of Haku—River Deity or Long-Lost Brother?

Haku is officially described as the spirit of the Kohaku River, who once saved Chihiro from drowning. Yet some fans believe he represents a brother who died rescuing her, citing the mother’s somewhat distant behavior toward Chihiro and Haku’s fierce protectiveness.

While no direct evidence in the film confirms this storyline, Miyazaki’s works often invite personal interpretations. Whether a guardian deity, a long-lost sibling, or both, Haku remains a powerful figure, driving Chihiro to find the courage she needs to save herself and her parents.

Familiar Ghibli Easter Eggs—Totoro on the Tracks?

Devoted fans often claim Spirited Away features cameo appearances from other Ghibli classics. The soot sprites (or susuwatari), known from My Neighbor Totoro, do appear here, fueling speculation that other characters, such as Satsuki and Mei, might also appear in the train scene.

Whether these sightings are real or imagination-fueled, Ghibli is no stranger to playful nods across its filmography. True or not, hunting for hidden references adds extra fun to every rewatch.

Historic Awards and Box Office Triumph

Before Spirited Away, no animated feature had won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. Its 2002 victory changed the global perception of anime, and the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature followed soon after, showcasing its worldwide appeal.

At home in Japan, the movie outperformed Hollywood heavyweights, becoming a cultural phenomenon. This success proved that animated films—especially from Ghibli—could hold their own against big-budget international blockbusters.

Playful Wordplay—Yubaba, Zenibaba, and More

Ghibli films often embed clever puns and name-based jokes. In Spirited Away, some fans note that “Yubaba” (the bathhouse witch) and her twin “Zenibaba” can form words like “Zeniyu” (coined from Japanese for “money” and “bath”) or reference “sentō” (public baths). Such linguistic twists underscore Miyazaki’s playful approach to naming.

“Lin” was also sketched in early concept art as a white fox or weasel, hinting at Ghibli’s fascination with shapeshifting beings and mysterious transformations—a recurring theme in many of its films.

The Audi A4 Cameo—Attention to Detail

In the opening sequence, Chihiro’s family drives to their new home in what appears to be an Audi A4. According to sources, Ghibli recorded actual engine and door sounds from a real Audi to capture authenticity, highlighting the studio’s trademark dedication to detail.

Realism Meets Fantasy: Even in a fantastical story, such small touches help ground the film, making magical realms like Aburaya feel that much more believable.

Environmental Messages and the Stink Spirit

Pollution has long been a concern in Miyazaki’s works, and Spirited Away is no exception. One of the film’s most memorable scenes involves the “Stink Spirit,” later revealed to be a polluted river god clogged with debris. Pulling out old bicycles and garbage dramatizes the harm humans inflict on nature.

In this sequence, viewers witness not only physical pollution but also humanity’s neglect of the environment. Through vivid imagery, Miyazaki once again calls attention to the importance of respecting the natural world.

Coming-of-Age Lessons—Don’t Look Back

Amid the film’s fantastical setting, its core message is undeniably human. Chihiro begins as a timid child, uncertain and fearful. By accepting challenges, learning responsibility, and facing the consequences of her actions, she transforms into someone who can stand on her own two feet.

The advice “Don’t look back” as she leaves the spirit world resonates on multiple levels—leaving behind regrets, moving on from past mistakes, and focusing on personal growth. This universal lesson is part of what makes Spirited Away so timeless: it speaks to anyone who has ever felt lost, reminding us to keep moving forward even when the path is unfamiliar.

Spirited Away is more than a beautifully drawn adventure—it’s a multilayered tapestry woven with social critiques, hidden references, and metaphors for real-world challenges. From rumored brothel themes to potential lost endings, this film sparks passionate debate and encourages repeat viewings that reveal fresh details each time.

In this second installment of our deep-dive series, we’ve explored fan theories, urban legends, and the deeper themes embedded in Miyazaki’s beloved work. Next up, in Part 3, we’ll tackle 13 of the most enduring mysteries surrounding Spirited Away, dissecting everything from cryptic character arcs to possible connections with other Ghibli favorites.

Until then, feel free to revisit Spirited Away with these insights in mind. You may be surprised how a single detail—like a subtle hand gesture or a shadowy figure in the background—can shift your entire perspective. After all, in a movie brimming with imagination, the more you look, the more you’ll discover.

Explore more articles about Spirited Away! Thank you!